The Roman Woman

NECROPOLIS OF PORTO

As the empire expanded, Rome needed its own seaport, leading Emperor Claudius in 42 AD to begin the construction of a harbor basin at the mouth of the Tiber. To improve the functionality of the Port of Claudius, which was silting up due to the advancing coastline, Emperor Trajan built a new hexagonal-shaped basin in 100 AD.

Around the port, a small settlement gradually developed, taking the name Portus. The new city of Porto remained vibrant for several centuries until natural events led to the entire area becoming marshland.

Upon their passing, the inhabitants of Porto were buried in a vast necropolis in use from the 1st to the 4th century AD.

The necropolis was discovered in 1925 during land reclamation works and was excavated and made accessible to visitors in the present-day district of Isola Sacra in Fiumicino.

Unlike the Etruscans, who built their tombs underground or, if above ground, concealed them under earth mounds — typically located outside city walls — the Romans constructed their tombs along the edges of major roads, such as the Necropolis of Porto in Fiumicino, near Via Portuense.

During the 2023/2024 school year, students from classes I^ A and I^ B of the Liceo Scientifico Paolo Baffi in Fiumicino, accompanied by teachers Eleonora Albanese and Floriana Contestabile, as well as a guide, visited the necropolis in search of tombs that reflected the wishes of Roman women to leave a lasting memory of themselves. In particular, they explored their desire for a personalized burial site, as well as the interest of men in constructing funerary monuments dedicated to the women of their families (wives, mothers, daughters, granddaughters).

Through the study of inscriptions and the observation of beautifully painted decorations, stone reliefs, and mosaics, it was possible to identify and reconstruct the lives of several women who lived in ancient Porto and were buried in its necropolis.

Walking through the burial grounds, one encounters numerous well-preserved tombs. Our story begins with Tomb No. 106, currently not visible, where a statue — now exhibited in the Ostia Museum — was discovered.

In the 2nd century AD, an elegant woman was buried in this monumental tomb, and we are fortunate to have her portrait preserved in the form of the statue.

Statue of Iulia Procula

This is Iulia Procula, as presented to us by the beautiful inscription. She chose to be depicted in the likeness of the goddess Hygieia, the deity of health. She likely lived in Portus and was buried by her mother, as indicated by the inscription found: IVLIAE TI (beri) F(iliae) PROCVLAE VIXIT ANN(is) XXIX MENS(ibus) XI MVNATIA HELPIS MATER FIL (iae) PIISSIMAE FEC(it).

Another tomb that caught our attention is number 100, belonging to a physician. On a relief applied to a wall, a midwife is depicted, named Scribonia Attice, possibly the wife of the physician. The depiction shows a woman giving birth while sitting on a birthing chair. The midwife assists and guides the woman through the delivery. Another woman is present, possibly for additional assistance or comfort, as only women were allowed in the birthing room.

Relief Depicting Scribonia Attice

The midwife (obstetrix), after delivering the baby (effusio), would ensure the child’s health and proceed to cut the umbilical cord.

On the tomb slab, it is written that Scribonia had this tomb built for herself, her husband, and their freedmen (libertis liber-tabusque posterisque eorum), emphasizing the familial nature of the burial.

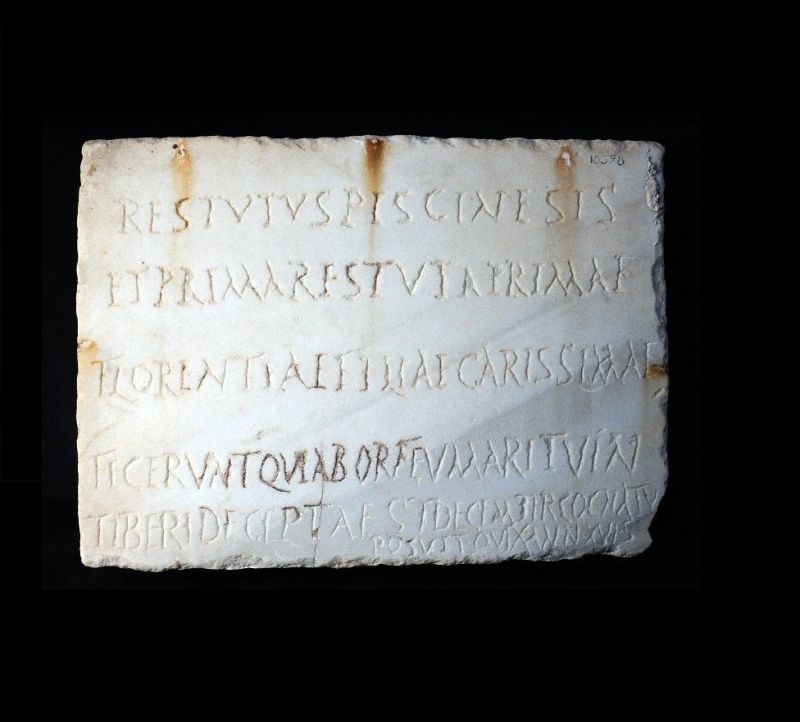

The funerary inscription of the tomb of Prima Florentia is also very interesting.

Funerary Inscription of the Tomb of Prima Florentia

The tombstone, very simple, contains only a few brief lines, which when translated into Italian read: “Restutus Piscinesis and Prima Restuta built this tomb for their dearest daughter Prima Florentia, who was thrown into the Tiber by her husband Orpheus. Her maternal uncle December placed it. She was 16 and a half years old.” These short and poignant words, written by the girl’s relatives, serve as a lasting memorial to a femicide that occurred nearly two thousand years ago, during the time of Imperial Rome, when the young Prima Florentia was thrown into the river by her husband. The reasons for this barbaric killing are unknown, as nothing else remains or is known about the bride, except for the funerary inscription.

Other artifacts found in the necropolis testify to the desire of men to honor the women of their family. These can now be found in various museum collections.

On one of these, a marble tomb cover, the following inscription was found: “The burial of Maria Semproniana, daughter of Marcus, was organized by her father, Marcus Marius Iulianus.”

Another cover provides the following information about a young woman who married at the age of thirteen: “Olimpo, a slave of Matidia, daughter of Augustus, built this monument for his Urbica, with whom he lived for one year, eight months, twenty-two days, and three hours, and who died at the age of fourteen years and eleven months.”

Tombs 75 and 76 bear a plaque with the inscription: “Aelia Salviana built the tomb for her meritorious slave Sabina, who was born in the house, and who lived six years, nine months, and twenty days.”

Exploring the open space next to the burial chamber of tomb 75, we read the following inscription on a marble cover: “The burial of Maria Semproniana, daughter of Marcus, was organized by her father, Marcus Marius Iulianus.”

Arriving at tomb 71, dating from the time of Trajan or Hadrian, we noticed the following inscription on a marble slab at the top of the pediment, which is the triangular or arched top of a facade: “Lucius Suallius Eupor built (this tomb) for Afrodisia, who was freed along with him, whom he held very dear and deserved it.”

On the marble slab of tomb 70, also dating from the time of Trajan or Hadrian, it is written: “This tomb was destined for Suallia Rhembas, the innocent, who died at the age of two years, five months, twenty-three days, and eight hours. The tomb was built by her father, Lucius Suallius Lupio.”

Walking through the streets of the necropolis, we came to tomb 66. It is a “box” tomb, and on its side facing the sea, there is a marble slab with the following inscription in irregular characters: “Cecilia Massima built the tomb for Socrates, son and grandson, paid for with the estate of Aurelia.” Socrates was likely the son of Cecilia Massima and the grandson of Aurelia. The tomb dates back to the time of Hadrian or Antoninus Pius.

Above the entrance of tomb no. 63, also dating from the time of Trajan, is the following inscription: “Publius Sestilius Pannichiano built this tomb for Alfia Procilla, daughter of Marcus, and for Claudia Igia, his beloved wives, and for himself and his heirs.” Evidently, the man had remarried.

Also from tomb no. 63, there is the following inscription: “This tomb was built by Marcus Licinius Hermes for Considia Saturnina, his beloved wife, and for himself.”

In front of tomb 60, in the “Field of the Poor,” a travertine slab with the following inscription was found: “(This tomb) was made by Pomponia Optata and Marcus Caecilius Euhodus, her father, for their pious daughter Pomponia Felix, who lived three years, eight months, and three days.” The inscription dates from the time of Hadrian.

On a wall of the “box” tomb no. 53, above a small entrance, there is a marble slab with the following writing: “The tomb was erected for the devoted son Marcus Valerius Fortunatus by his mother Sergia Ianuaria, but also for herself and her family. The son died at the age of three years, eight months, and twenty-five days.”

Of tomb 49, only the facade is visible. Here, a marble slab was found with the following inscription in small characters: “Tiberius Claudius Eumene, freedman of the emperor (has erected this monument) for himself and for Claudia Febe and Fadia Teti, his daughters, and Claudius Febo, his son, and Iulia Heuresis, his wife, and their children.”

Tombs 13, 14, and 15 are part of a facade. Above the entrance, there is a marble slab with the following inscription: “Roscia Selene erected the tomb for herself and for her son Marcus Roscius Sentianus, for her freed slaves, and for her descendants.”

During the excavations of tomb no. 4, in the area that expanded it, two burials were discovered. One of them was built by a freedwoman for herself and for her patron Gorgia. Inside the tomb, two bodies were buried, one above the other, a case of epithesis. The tomb was evidently closed after the first burial and later reopened to bury the woman who died afterward. Among her bones, a set of gold earrings was found.

The focus of the path has intentionally concentrated on certain burials where emotional significance is predominant, and where it is possible to identify a recurring typology: that of young women who died prematurely, for whom a husband or a parent dedicated the tomb.

The attached photographic collection shows only part of the great appeal of the necropolis, which, through the particular perspective represented by the illustrated burials, seeks to demonstrate the desire of women to leave a trace of themselves through a “personalized” tomb, in an era when women did not even have the right to own a proper name. The narrative journey will continue with the aim of highlighting the role of women in society during the Roman Imperial period.

The Roman Woman

NECROPOLIS OF PORTO

As the empire expanded, Rome needed its own seaport, leading Emperor Claudius in 42 AD to begin the construction of a harbor basin at the mouth of the Tiber. To improve the functionality of the Port of Claudius, which was silting up due to the advancing coastline, Emperor Trajan built a new hexagonal-shaped basin in 100 AD.

Around the port, a small settlement gradually developed, taking the name Portus. The new city of Porto remained vibrant for several centuries until natural events led to the entire area becoming marshland.

Upon their passing, the inhabitants of Porto were buried in a vast necropolis in use from the 1st to the 4th century AD.

The necropolis was discovered in 1925 during land reclamation works and was excavated and made accessible to visitors in the present-day district of Isola Sacra in Fiumicino.

Unlike the Etruscans, who built their tombs underground or, if above ground, concealed them under earth mounds — typically located outside city walls — the Romans constructed their tombs along the edges of major roads, such as the Necropolis of Porto in Fiumicino, near Via Portuense.

During the 2023/2024 school year, students from classes I^ A and I^ B of the Liceo Scientifico Paolo Baffi in Fiumicino, accompanied by teachers Eleonora Albanese and Floriana Contestabile, as well as a guide, visited the necropolis in search of tombs that reflected the wishes of Roman women to leave a lasting memory of themselves. In particular, they explored their desire for a personalized burial site, as well as the interest of men in constructing funerary monuments dedicated to the women of their families (wives, mothers, daughters, granddaughters).

Through the study of inscriptions and the observation of beautifully painted decorations, stone reliefs, and mosaics, it was possible to identify and reconstruct the lives of several women who lived in ancient Porto and were buried in its necropolis.

Walking through the burial grounds, one encounters numerous well-preserved tombs. Our story begins with Tomb No. 106, currently not visible, where a statue — now exhibited in the Ostia Museum — was discovered.

In the 2nd century AD, an elegant woman was buried in this monumental tomb, and we are fortunate to have her portrait preserved in the form of the statue.

Statue of Iulia Procula

This is Iulia Procula, as presented to us by the beautiful inscription. She chose to be depicted in the likeness of the goddess Hygieia, the deity of health. She likely lived in Portus and was buried by her mother, as indicated by the inscription found: IVLIAE TI (beri) F(iliae) PROCVLAE VIXIT ANN(is) XXIX MENS(ibus) XI MVNATIA HELPIS MATER FIL (iae) PIISSIMAE FEC(it).

Another tomb that caught our attention is number 100, belonging to a physician. On a relief applied to a wall, a midwife is depicted, named Scribonia Attice, possibly the wife of the physician. The depiction shows a woman giving birth while sitting on a birthing chair. The midwife assists and guides the woman through the delivery. Another woman is present, possibly for additional assistance or comfort, as only women were allowed in the birthing room.

Relief Depicting Scribonia Attice

The midwife (obstetrix), after delivering the baby (effusio), would ensure the child’s health and proceed to cut the umbilical cord.

On the tomb slab, it is written that Scribonia had this tomb built for herself, her husband, and their freedmen (libertis liber-tabusque posterisque eorum), emphasizing the familial nature of the burial.

The funerary inscription of the tomb of Prima Florentia is also very interesting.

Funerary Inscription of the Tomb of Prima Florentia

The tombstone, very simple, contains only a few brief lines, which when translated into Italian read: “Restutus Piscinesis and Prima Restuta built this tomb for their dearest daughter Prima Florentia, who was thrown into the Tiber by her husband Orpheus. Her maternal uncle December placed it. She was 16 and a half years old.” These short and poignant words, written by the girl’s relatives, serve as a lasting memorial to a femicide that occurred nearly two thousand years ago, during the time of Imperial Rome, when the young Prima Florentia was thrown into the river by her husband. The reasons for this barbaric killing are unknown, as nothing else remains or is known about the bride, except for the funerary inscription.

Other artifacts found in the necropolis testify to the desire of men to honor the women of their family. These can now be found in various museum collections.

On one of these, a marble tomb cover, the following inscription was found: “The burial of Maria Semproniana, daughter of Marcus, was organized by her father, Marcus Marius Iulianus.”

Another cover provides the following information about a young woman who married at the age of thirteen: “Olimpo, a slave of Matidia, daughter of Augustus, built this monument for his Urbica, with whom he lived for one year, eight months, twenty-two days, and three hours, and who died at the age of fourteen years and eleven months.”

Tombs 75 and 76 bear a plaque with the inscription: “Aelia Salviana built the tomb for her meritorious slave Sabina, who was born in the house, and who lived six years, nine months, and twenty days.”

Exploring the open space next to the burial chamber of tomb 75, we read the following inscription on a marble cover: “The burial of Maria Semproniana, daughter of Marcus, was organized by her father, Marcus Marius Iulianus.”

Arriving at tomb 71, dating from the time of Trajan or Hadrian, we noticed the following inscription on a marble slab at the top of the pediment, which is the triangular or arched top of a facade: “Lucius Suallius Eupor built (this tomb) for Afrodisia, who was freed along with him, whom he held very dear and deserved it.”

On the marble slab of tomb 70, also dating from the time of Trajan or Hadrian, it is written: “This tomb was destined for Suallia Rhembas, the innocent, who died at the age of two years, five months, twenty-three days, and eight hours. The tomb was built by her father, Lucius Suallius Lupio.”

Walking through the streets of the necropolis, we came to tomb 66. It is a “box” tomb, and on its side facing the sea, there is a marble slab with the following inscription in irregular characters: “Cecilia Massima built the tomb for Socrates, son and grandson, paid for with the estate of Aurelia.” Socrates was likely the son of Cecilia Massima and the grandson of Aurelia. The tomb dates back to the time of Hadrian or Antoninus Pius.

Above the entrance of tomb no. 63, also dating from the time of Trajan, is the following inscription: “Publius Sestilius Pannichiano built this tomb for Alfia Procilla, daughter of Marcus, and for Claudia Igia, his beloved wives, and for himself and his heirs.” Evidently, the man had remarried.

Also from tomb no. 63, there is the following inscription: “This tomb was built by Marcus Licinius Hermes for Considia Saturnina, his beloved wife, and for himself.”

In front of tomb 60, in the “Field of the Poor,” a travertine slab with the following inscription was found: “(This tomb) was made by Pomponia Optata and Marcus Caecilius Euhodus, her father, for their pious daughter Pomponia Felix, who lived three years, eight months, and three days.” The inscription dates from the time of Hadrian.

On a wall of the “box” tomb no. 53, above a small entrance, there is a marble slab with the following writing: “The tomb was erected for the devoted son Marcus Valerius Fortunatus by his mother Sergia Ianuaria, but also for herself and her family. The son died at the age of three years, eight months, and twenty-five days.”

Of tomb 49, only the facade is visible. Here, a marble slab was found with the following inscription in small characters: “Tiberius Claudius Eumene, freedman of the emperor (has erected this monument) for himself and for Claudia Febe and Fadia Teti, his daughters, and Claudius Febo, his son, and Iulia Heuresis, his wife, and their children.”

Tombs 13, 14, and 15 are part of a facade. Above the entrance, there is a marble slab with the following inscription: “Roscia Selene erected the tomb for herself and for her son Marcus Roscius Sentianus, for her freed slaves, and for her descendants.”

During the excavations of tomb no. 4, in the area that expanded it, two burials were discovered. One of them was built by a freedwoman for herself and for her patron Gorgia. Inside the tomb, two bodies were buried, one above the other, a case of epithesis. The tomb was evidently closed after the first burial and later reopened to bury the woman who died afterward. Among her bones, a set of gold earrings was found.

The focus of the path has intentionally concentrated on certain burials where emotional significance is predominant, and where it is possible to identify a recurring typology: that of young women who died prematurely, for whom a husband or a parent dedicated the tomb.

The attached photographic collection shows only part of the great appeal of the necropolis, which, through the particular perspective represented by the illustrated burials, seeks to demonstrate the desire of women to leave a trace of themselves through a “personalized” tomb, in an era when women did not even have the right to own a proper name. The narrative journey will continue with the aim of highlighting the role of women in society during the Roman Imperial period.