Environment: Territory and Landscape of Fiumicino

The territory of Fiumicino features two main landscapes with distinct morphologies: the coastal plain and the inland hills. Using the Roma-Civitavecchia (A12) motorway as a boundary line, one notices that the area to the west of the road is predominantly flat, while to the east it becomes hilly. This morphological difference is the result of geological events that occurred between the late Pliocene and the Pleistocene.

The flat terrain, in reality, retains a series of low elevations, no more than 8 meters above sea level, interspersed with shallow depressions. These formations consist of dune ridges, more or less parallel, locally known as tumuleti.

The dune belt, formed by sandy sediments carried to the sea by the Tiber River over the past 2,000 years and subsequently reshaped by waves and wind, stretches inland from the coastline for about 2 to 4 kilometers. This is where the towns of Fiumicino, Focene, and Fregene were built.

As one moves closer to the motorway, the elevation decreases, and the terrain changes: sand grains become finer, and the sediment becomes richer in clay, silt, and peat. This area preserves remnants, along with a dense network of artificial canals, of an ancient system of coastal lakes known as Pagliete, Maccarese, and Porto.

The contribution of the Tiber delta to the formation of this area is significant, extending over at least 180 km².

The repeated oscillations of the sea level caused temporary exposure of the seabed until the Lower Pleistocene, during which the continuous uplift of the areas behind the present Tyrrhenian coast led to significant paleogeographic changes, resulting in the formation of fluvio-marsh environments.

With the onset of volcanic activity (approximately 600,000 years ago) of the Sabatini volcanoes to the northwest and the Alban Hills to the southeast, the landscape underwent a radical transformation: valleys were filled in, elevations were covered, and watercourses were diverted by thick layers of tuff, ash, lapilli, and pumice.

Around 18,000 years ago, at the end of the last glaciation (Würm), the sea level was approximately 120 meters lower than it is today, and the coastline likely lay at least 10 kilometers farther out. With the melting of polar and mountain ice caps, caused by the return to milder climatic conditions, the sea level slowly began to rise, once again flooding the area. This event caused the Tiber River’s mouth to retreat significantly, flowing into a large lagoon separated from the open sea by a series of discontinuous coastal barriers aligned parallel to the coast.

From the hills behind the towns of Focene and Fregene, streams, likely including the Arrone River, flowed down and deposited sediments into the lagoon, contributing to its infilling. Today, the ancient lagoon is entirely reclaimed, leaving behind only a network of former coastal lakes.

The Local Natural Capital: Natura 2000 Network and Protected Areas

The territory of Fiumicino includes an extensive network of areas with high natural value, hosting species and habitats of significant importance according to the Habitats Directive.

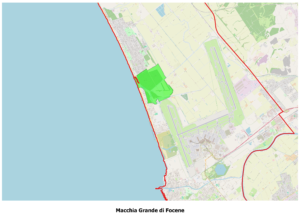

SIC (Site of Community Importance) Macchia Grande di Focene and Macchia dello Stagneto (IT6030023)

This site belongs to the Mediterranean biogeographical region, covering an area of 317 hectares. It is located in the Province of Rome and falls entirely within the municipality of Fiumicino.

The site is fully included in the protected area of the Riserva Naturale Statale Litorale Romano, established by decree of the Ministry of the Environment on March 29, 1996. Part of the Site of Community Importance, it has been part of the network of Oases managed by WWF Italy since 1986.

The habitats and species present in the SIC include:

| 1210 | Annual vegetation of marine deposit lines |

| 1410 | Mediterranean flooded grasslands (Juncetalia maritimi) |

| 2110 | Embryonic mobile dunes |

| 2120 | Mobile dunes of the coastal ridge with Ammophila arenaria (white dunes) |

| 2130 | Fixed coastal dunes (Crucianellion maritimae) |

| 2230 | Dunes with Malcolmietalia grasslands |

| 2250* | Coastal dunes with Juniperus spp. |

| 2260 | Dunes with Cisto-Lavanduletalia scrub vegetation |

| 2270* | Dune forests of Pinus pinea and Pinus pinaster |

| 9340 | Forests of Quercus ilex and Quercus rotundifolia |

| 2220 | Emys orbicularis – European pond turtle |

| 1217 | Testudo hermanni – Hermann’s tortoise |

The most significant pressures and threats typically affect coastal habitats and arise mainly from the improper use of these areas. The dune area, in particular, is subject to high anthropogenic pressure, primarily due to the considerable population increase during the bathing season and recreational activities.

Moreover, the extraction of surface water and groundwater (drainage and lowering of the water table), which causes saltwater intrusion, poses a severe threat to the habitats within the SIC.

Additionally, the ZPS Lago di Traiano (IT6030026) and the SIC Isola Sacra (IT6030024) are contiguous to the area covered by this contract.

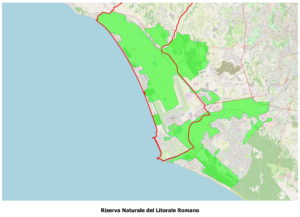

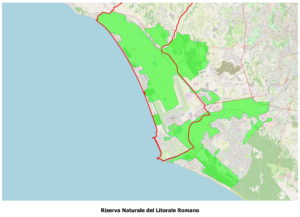

State Nature Reserve of the Roman Coastline

The Riserva Naturale Statale del Litorale Romano was established by the Ministry of the Environment with a decree dated March 29, 1996, pursuant to Law 394/91. It encompasses natural environments, areas of historical and archaeological interest, and agricultural lands in the areas of Rome and Fiumicino, stretching from the Palidoro coastline to the Capocotta beach.

Within the Reserve’s territory are three Sites of Community Importance (SIC) and two Special Protection Areas (ZPS):

SIC IT6030025: Macchia Grande di Ponte Galeria

SIC IT6030023: Macchia Grande di Focene e Macchia dello Stagneto

SIC IT6030027: Castel Porziano (coastal area)

ZPS IT6030026: Lago di Traiano

ZPS IT6030084: Castel Porziano (Presidential Estate)

For the area relevant to this management plan, the Reserve’s administration is entrusted to the Municipality of Fiumicino. The Reserve spans approximately 16,000 hectares, roughly halved between the municipalities of Rome and Fiumicino.

As specified in the decree and the “Management Plan of the State Nature Reserve of the Roman Coastline,” the Reserve’s territory is divided into Type 1 and Type 2 areas. In the former, construction is strictly prohibited, except for conservation purposes, as they are characterized by high natural, landscape, and archaeological value. In contrast, interventions necessary for managing the land while respecting its use are allowed in the latter.

The Reserve’s territory is divided into six categories based on environmental, naturalistic, and socio-cultural components:

Agricultural areas

Coastal areas

Natural and semi-natural woodland areas

Hydrographic areas

Residential areas

Tourism/archaeological areas

These categories form a coherent framework of significant elements representing the distinctive value of the Reserve. They allow to identify priority habitats, animal population nuclei, biotic communities, agroecosystems, and landscapes that require conservation to maintain the functionality of their respective categories.

Based on a set of parameters, 21 Management Units (UdG) have been identified, of which 12 are within the Municipality of Fiumicino. Some of these overlap with interventions in the Contratto di Fiume Arrone (Arrone River Agreement):

UdG of Bonifica di Maccarese;

General guidelines for the Coastal Area;

UdG of Dune di Passoscuro (dunes of Passoscuro);

UdG of Bocca di Leone, Bosco Cesolina, Dune di Focene, and Foce del Rio Tre Denari;

UdG of the Watercourses north of Fiumicino;

UdG of Vasche di Maccarese.

Each UdG has a project sheet summarizing its defining landscape and environmental characteristics, challenges, ongoing territorial dynamics, and precise management guidelines. Among the species present is the cattle egret (Bubulcus ibis), which has become increasingly common in the area of interest.

The "Blue Network" (Marine): The Coastal Zone

Among terrestrial environments, coastal areas are those that have been most affected by the lack of adequate development policies, partly because their importance for territorial protection was recognized late.

The areas that have preserved some degree of naturalness over time are primarily found at the mouths of both natural and artificial waterways. Consequently, remnants of mobile dune vegetation still exist along the coast. This vegetation plays a crucial protective role against erosion, safeguarding the environment behind it and the beaches.

The mobile dune environment is of significant scientific interest due to the unique adaptations of the species that inhabit it, known as psammophytes, which are becoming increasingly rare along our coastlines. In some short stretches (such as at the mouth of the Rio Tre Denari, the Fosso Palidoro, or the Fiume Arrone), which have escaped illegal construction, hints of consolidated dunes can still be observed. These dunes are characterized by the presence of juniper (Juniperus macrocarpa), followed by mastic tree (Pistacia lentiscus), mock privet (Phillyrea latifolia), and other species.

It is not always possible to find all four zones that define the mobile dune environment together, as dunes are generally in a state of severe erosion, with small tufts of vegetation clinging to the tops of sand pinnacles. Nonetheless, given the high dynamism of dune vegetation, limited environmental restoration efforts and a few years of integrated protection—particularly to reduce trampling—could restore these areas of interest to a good state of naturalness.

Identity Agricultural Areas

Historically, the Arrone River served as the boundary between the Etruscan and Roman civilizations. With the rise of Christianity, at the point where it intersects the Via Aurelia, the river marked the boundary between the dioceses of Porto, Caere, and Selva Candida. At the mouth of the Arrone stood a port which, along with the maritime hubs of Pyrgi and Casto Nova, formed the port system of Caere. The heights and riverbed of the Arrone are rich in archaeological sites from various periods. An example is the Pleistocene fluvial deposit known as the Polledrara site, which contains fossil remains of the ancient elephant and the aurochs. Some hypotheses, based on specific archaeological findings, suggest that the Arrone Valley was of strategic importance as a connection between Upper Lazio and the salt pans of Maccarese. Given the significance of this area, both the Lazio Region and the Ministry of Cultural and Environmental Heritage (MiBAC) included the Arrone River Valley, the Rio Palidoro and Fosso delle Cadute valleys, and the Furbara Plain in the so-called Identity Agricultural Areas in the Regional Territorial Landscape Plan (PTPR).

The regional document describes the Arrone River Valley and the Fosso di Santa Maria di Galeria as follows: “The area, located between the volcanic complex of the Sabatini Mountains and the Roman Coast Maremma, stretches between Lake Bracciano and the coastal strip near Fiumicino, in the locality of Torre in Pietra. The abundance of water has been one of the great resources of Rome and its territory since its origins. From the Sabatini Mountains to the Boccea plateau, the Arrone River flows, its name derived from the Etruscan root ‘aruns’“. It originates from Lake Bracciano and, after a course of about 37 km, empties into the sea near Maccarese. Based on its geological features, the Arrone basin can be divided into three parts. The upper part, located just south of Lake Bracciano, has a hilly morphology typical of the volcanic reliefs of the region. In the central part, watercourses have carved deep valley incisions and reached the sedimentary layers beneath the volcanic deposits, creating a system of elongated hills. The area includes that part of the valley that represents the transition zone to the coastal plain.

The entire area is a territorial complex of great environmental diversity, where naturalistic river valleys alternate with a vast area of gently rolling hills influenced by the climatic effects of the nearby coastal area. The Arrone Valley, with its resources, has been the site of numerous human settlements tied particularly to rural and agricultural use of the land, evidenced by the Etruscan city known as Galeria, later colonized by the Romans as an agricultural village. By the late 1700s, the village was abandoned, likely due to malaria, and its inhabitants moved approximately 4 km away, founding what is now Santa Maria di Galeria Nuova.

The landscape of the Arrone Valley reflects the Roman countryside of the past century, with pastures, meadows, woods, and hedges alternating with cultivated areas. The landscape, after the hilly area, widens considerably near the confluence of the basin, becoming flat and rich in alluvial deposits. South of the Via Aurelia, the watercourse traverses its final stretch before reaching the sea.

The Arrone Valley has been a focal point for human habitation for thousands of years, as evidenced by prehistoric findings near the emissary’s source and the lower Arrone. A fundamental component of the area is the Castel di Guido complex and its surroundings, a geologically uniform area of significant archaeological, environmental, and scenic interest. Particularly, the current village holds historical and archaeological importance, representing continuous settlement from Roman times to the present day. Another historically and scenically significant area is the Leprignana Estate with its rural centers, a testament to the Roman reclamation of Torre in Pietra (1926–45) led by Senator Albertini.

The land reclamation and the establishment of the rural centers (or Units) of the estate’s productive enterprise shape a unified settlement plan, which varies according to the specialized activities carried out. The agricultural landscape resulting from the reclamation remains relatively intact and stands as a testament to a high-quality territorial agricultural organization designed in its complexity and entirety, including the foundation and decentralization of new housing and rural infrastructure.”

Further north, the Rio Palidoro and Fosso delle Cadute Valleys, the modern boundary between the municipalities of Fiumicino and Cerveteri, extend towards the plain. Although smaller in area, these valleys also impact the municipalities of Bracciano, Anguillara Sabazia, and Rome. The area between the Sabatini Mountains volcanic complex and the Roman Coast Maremma is described as follows:

“The Rio Palidoro Valley resembles the adjacent Arrone Valley in its orthogonal orientation to the coastline and as part of the watercourse network that is a vital resource for Rome and its territory. The Rio Palidoro originates from the Sabatini Mountains and flows into the Tyrrhenian Sea near Passo Oscuro. The ecosystem of the pre-hill areas between Lake Bracciano and the Tyrrhenian Sea constitutes a highly important landscape and natural ensemble. With its orographic sequence from pre-coastal areas to volcanic hills interspersed with wetlands, it is the last preserved example of the typical southern Lazio Maremma landscape. It transitions from reclaimed, orderly agricultural land to ravines and cultivated fields, showcasing a diverse horizon of small uplands that include sites of ancient history, castles, farmhouses, and archaeological remains. The flat areas alternate with the hills, serving as a prelude to the view of the Monti Sabatini in a continuous and fluid manner, connecting the varied and fragmented landscape of the small elevations overlooking Lake Bracciano to the northeast with the vast coastal plain extending toward the Tyrrhenian Sea.”

Rural Environment

In a large area of Fiumicino, the prevailing landscape is rural, characterized by its regular subdivision, the management of water through numerous canals, the hydroelectric plants dating back to the late 19th century, such as the one in Focene, and the typical scattered settlement pattern of farmhouses and/or small rural centers. Here, alongside residential buildings, one can find structures for housing animals, storing tools, and preserving food supplies—distinct features of reclaimed areas.

The large Maccarese-Pagliete plain, covering an area of over 4,500 hectares, was the first to undergo comprehensive reclamation. The Torrimpietra estate to the northeast and, further beyond, the Palidoro estate—both adjacent to the hilly inland areas subject to the Agricultural Reform of the 1950s—share a common history.

Different events that shared a common thread in the wake of the country’s unification: a period of profound and radical changes in the territory. Within a few decades, these transformations deeply altered environments and landscapes, the economy, and the lives of the inhabitants, almost entirely erasing the ancient and long-standing system of large estates. These estates had coexisted with vast wetlands and marshy areas, giving rise to a form of semi-nomadic pastoralism and an agriculture confined to small plots, supporting a sparse, mostly seasonal population that migrated in response to the rhythms of fieldwork and the cycles of malaria.

These more archaic rural landscapes are still visible today in residual areas of the original vast natural lagoon system behind the dune system—now protected as areas of particular value.

The recognizability of the reclaimed landscape, which has remained largely intact, is undoubtedly due to the presence of vegetational elements such as windbreak rows of eucalyptus trees, the regular subdivision of plots, demarcated by drainage and irrigation canals, and the dense network of inter-farm roads. The almost unchanged system of settlement within agricultural centers and farmhouses also contributes to this recognition.

This vast real estate heritage, despite the differences and particularities that distinguish various reclamation projects, has now for nearly a century been an indispensable and strongly identity-defining component of the entire territory. It is perceived as such by the communities living within it, as well as by those who, in different capacities, benefit from its beauty.

Maccarese Reclamation (1925-1938)

Following the first hydraulic reclamation between 1884 and 1889, which involved the hydraulic system’s adjustment and the construction of the water pumps, and later the full reclamation and the creation of the road network, around forty rural centers were designed and constructed, along with farms and facilities for processing and marketing products.

Each center was initially conceived and designed as an autonomous and self-sufficient agricultural unit, featuring residential buildings, stables, silos, warehouses, as well as areas for product processing, an oven, a fountain, and an outdoor space for a garden and vegetable patch, always accompanied by numerous trees.

The architecture of the agricultural centers—whose profile remains the most evident characteristic of the reclamation landscape today—was simple in form and closely aligned with functional needs. The construction techniques and materials used were typical of the landscapes of the Po Valley, from which many of the colonist families initially came.

Torrimpietra Reclamation (1927-1940)

The protagonists of the reclamation were Senator Luigi Albertini, Leonardo Albertini, and Niccolò Carandini, who relied on qualified professionals, specialized workers, and laborers for its realization.

The main innovation was in the organization and planning of the land, viewed in its entirety, with a new approach to housing and rural construction. This shift from temporary to permanent architecture led to the creation of productive units organized in “centers.”

The reclamation and construction of rural centers is the result of a collective effort, which includes, notably in the general architectural design, the work of architect Michele Busiri-Vici, who also restored the Falconieri Castle, which later became the headquarters of the Torrimpietra estate.

The creation of the centers gave form to a unified settlement project, with units differentiating based on the specialized activities they performed. Residential buildings were organized around an open courtyard with a central fountain, and technical buildings were situated in adjacent areas, arranged according to functional and hygienic needs.

To an initial core of centers (Falconieri, Tre Denari, Granaretto, Aurelia, Arenaro, Sant’Angelo), we must add the later settlements of the Tenuta della Leprignana (Breccia, Casetta Cavalle, Quarticciolo Barbabianca, Casal Bruciata). All of these bear witness to a social and economic reality that took architectural form, shaping a phase of territorial transformation in continuity with the past while establishing new rules that today represent one of the key identity markers of the area.

Palidoro Reclamation (1930-1938)

The more than 400 hectares that make up the Palidoro estate, at the time of reclamation, were part of the larger land complex owned by the Pio Istituto S. Spirito.

In terms of timing, the reclamation intervention was the last carried out in the plain stretching from Fiumicino to Ladispoli. The land is crossed by the Via Aurelia, which divides it into a flat part that slopes from the Rome-Civitavecchia railway line to the sea, and a hilly part of great environmental and naturalistic interest.

In this context, the reclamation, which began at the end of the 1920s and ended in 1938, led to the construction of various real estate units, each surrounded by a sufficiently large plot of land to meet the needs of the family unit. Historically, the estates have been allocated to tenants, a practice still in place today.

Environment: Territory and Landscape of Fiumicino

The territory of Fiumicino features two main landscapes with distinct morphologies: the coastal plain and the inland hills. Using the Roma-Civitavecchia (A12) motorway as a boundary line, one notices that the area to the west of the road is predominantly flat, while to the east it becomes hilly. This morphological difference is the result of geological events that occurred between the late Pliocene and the Pleistocene.

The flat terrain, in reality, retains a series of low elevations, no more than 8 meters above sea level, interspersed with shallow depressions. These formations consist of dune ridges, more or less parallel, locally known as tumuleti.

The dune belt, formed by sandy sediments carried to the sea by the Tiber River over the past 2,000 years and subsequently reshaped by waves and wind, stretches inland from the coastline for about 2 to 4 kilometers. This is where the towns of Fiumicino, Focene, and Fregene were built.

As one moves closer to the motorway, the elevation decreases, and the terrain changes: sand grains become finer, and the sediment becomes richer in clay, silt, and peat. This area preserves remnants, along with a dense network of artificial canals, of an ancient system of coastal lakes known as Pagliete, Maccarese, and Porto.

The contribution of the Tiber delta to the formation of this area is significant, extending over at least 180 km².

The repeated oscillations of the sea level caused temporary exposure of the seabed until the Lower Pleistocene, during which the continuous uplift of the areas behind the present Tyrrhenian coast led to significant paleogeographic changes, resulting in the formation of fluvio-marsh environments.

With the onset of volcanic activity (approximately 600,000 years ago) of the Sabatini volcanoes to the northwest and the Alban Hills to the southeast, the landscape underwent a radical transformation: valleys were filled in, elevations were covered, and watercourses were diverted by thick layers of tuff, ash, lapilli, and pumice.

Around 18,000 years ago, at the end of the last glaciation (Würm), the sea level was approximately 120 meters lower than it is today, and the coastline likely lay at least 10 kilometers farther out. With the melting of polar and mountain ice caps, caused by the return to milder climatic conditions, the sea level slowly began to rise, once again flooding the area. This event caused the Tiber River’s mouth to retreat significantly, flowing into a large lagoon separated from the open sea by a series of discontinuous coastal barriers aligned parallel to the coast.

From the hills behind the towns of Focene and Fregene, streams, likely including the Arrone River, flowed down and deposited sediments into the lagoon, contributing to its infilling. Today, the ancient lagoon is entirely reclaimed, leaving behind only a network of former coastal lakes.

The Local Natural Capital: Natura 2000 Network and Protected Areas

The territory of Fiumicino includes an extensive network of areas with high natural value, hosting species and habitats of significant importance according to the Habitats Directive.

SIC (Site of Community Importance) Macchia Grande di Focene and Macchia dello Stagneto (IT6030023)

This site belongs to the Mediterranean biogeographical region, covering an area of 317 hectares. It is located in the Province of Rome and falls entirely within the municipality of Fiumicino.

The site is fully included in the protected area of the Riserva Naturale Statale Litorale Romano, established by decree of the Ministry of the Environment on March 29, 1996. Part of the Site of Community Importance, it has been part of the network of Oases managed by WWF Italy since 1986.

The habitats and species present in the SIC include:

| 1210 | Annual vegetation of marine deposit lines |

| 1410 | Mediterranean flooded grasslands (Juncetalia maritimi) |

| 2110 | Embryonic mobile dunes |

| 2120 | Mobile dunes of the coastal ridge with Ammophila arenaria (white dunes) |

| 2130 | Fixed coastal dunes (Crucianellion maritimae) |

| 2230 | Dunes with Malcolmietalia grasslands |

| 2250* | Coastal dunes with Juniperus spp. |

| 2260 | Dunes with Cisto-Lavanduletalia scrub vegetation |

| 2270* | Dune forests of Pinus pinea and Pinus pinaster |

| 9340 | Forests of Quercus ilex and Quercus rotundifolia |

| 2220 | Emys orbicularis – European pond turtle |

| 1217 | Testudo hermanni – Hermann’s tortoise |

The most significant pressures and threats typically affect coastal habitats and arise mainly from the improper use of these areas. The dune area, in particular, is subject to high anthropogenic pressure, primarily due to the considerable population increase during the bathing season and recreational activities.

Moreover, the extraction of surface water and groundwater (drainage and lowering of the water table), which causes saltwater intrusion, poses a severe threat to the habitats within the SIC.

Additionally, the ZPS Lago di Traiano (IT6030026) and the SIC Isola Sacra (IT6030024) are contiguous to the area covered by this contract.

State Nature Reserve of the Roman Coastline

The Riserva Naturale Statale del Litorale Romano was established by the Ministry of the Environment with a decree dated March 29, 1996, pursuant to Law 394/91. It encompasses natural environments, areas of historical and archaeological interest, and agricultural lands in the areas of Rome and Fiumicino, stretching from the Palidoro coastline to the Capocotta beach.

Within the Reserve’s territory are three Sites of Community Importance (SIC) and two Special Protection Areas (ZPS):

SIC IT6030025: Macchia Grande di Ponte Galeria

SIC IT6030023: Macchia Grande di Focene e Macchia dello Stagneto

SIC IT6030027: Castel Porziano (coastal area)

ZPS IT6030026: Lago di Traiano

ZPS IT6030084: Castel Porziano (Presidential Estate)

For the area relevant to this management plan, the Reserve’s administration is entrusted to the Municipality of Fiumicino. The Reserve spans approximately 16,000 hectares, roughly halved between the municipalities of Rome and Fiumicino.

As specified in the decree and the “Management Plan of the State Nature Reserve of the Roman Coastline,” the Reserve’s territory is divided into Type 1 and Type 2 areas. In the former, construction is strictly prohibited, except for conservation purposes, as they are characterized by high natural, landscape, and archaeological value. In contrast, interventions necessary for managing the land while respecting its use are allowed in the latter.

The Reserve’s territory is divided into six categories based on environmental, naturalistic, and socio-cultural components:

Agricultural areas

Coastal areas

Natural and semi-natural woodland areas

Hydrographic areas

Residential areas

Tourism/archaeological areas

These categories form a coherent framework of significant elements representing the distinctive value of the Reserve. They allow to identify priority habitats, animal population nuclei, biotic communities, agroecosystems, and landscapes that require conservation to maintain the functionality of their respective categories.

Based on a set of parameters, 21 Management Units (UdG) have been identified, of which 12 are within the Municipality of Fiumicino. Some of these overlap with interventions in the Contratto di Fiume Arrone (Arrone River Agreement):

UdG of Bonifica di Maccarese;

General guidelines for the Coastal Area;

UdG of Dune di Passoscuro (dunes of Passoscuro);

UdG of Bocca di Leone, Bosco Cesolina, Dune di Focene, and Foce del Rio Tre Denari;

UdG of the Watercourses north of Fiumicino;

UdG of Vasche di Maccarese.

Each UdG has a project sheet summarizing its defining landscape and environmental characteristics, challenges, ongoing territorial dynamics, and precise management guidelines. Among the species present is the cattle egret (Bubulcus ibis), which has become increasingly common in the area of interest.

The "Blue Network" (Marine): The Coastal Zone

Among terrestrial environments, coastal areas are those that have been most affected by the lack of adequate development policies, partly because their importance for territorial protection was recognized late.

The areas that have preserved some degree of naturalness over time are primarily found at the mouths of both natural and artificial waterways. Consequently, remnants of mobile dune vegetation still exist along the coast. This vegetation plays a crucial protective role against erosion, safeguarding the environment behind it and the beaches.

The mobile dune environment is of significant scientific interest due to the unique adaptations of the species that inhabit it, known as psammophytes, which are becoming increasingly rare along our coastlines. In some short stretches (such as at the mouth of the Rio Tre Denari, the Fosso Palidoro, or the Fiume Arrone), which have escaped illegal construction, hints of consolidated dunes can still be observed. These dunes are characterized by the presence of juniper (Juniperus macrocarpa), followed by mastic tree (Pistacia lentiscus), mock privet (Phillyrea latifolia), and other species.

It is not always possible to find all four zones that define the mobile dune environment together, as dunes are generally in a state of severe erosion, with small tufts of vegetation clinging to the tops of sand pinnacles. Nonetheless, given the high dynamism of dune vegetation, limited environmental restoration efforts and a few years of integrated protection—particularly to reduce trampling—could restore these areas of interest to a good state of naturalness.

Identity Agricultural Areas

Historically, the Arrone River served as the boundary between the Etruscan and Roman civilizations. With the rise of Christianity, at the point where it intersects the Via Aurelia, the river marked the boundary between the dioceses of Porto, Caere, and Selva Candida. At the mouth of the Arrone stood a port which, along with the maritime hubs of Pyrgi and Casto Nova, formed the port system of Caere. The heights and riverbed of the Arrone are rich in archaeological sites from various periods. An example is the Pleistocene fluvial deposit known as the Polledrara site, which contains fossil remains of the ancient elephant and the aurochs. Some hypotheses, based on specific archaeological findings, suggest that the Arrone Valley was of strategic importance as a connection between Upper Lazio and the salt pans of Maccarese. Given the significance of this area, both the Lazio Region and the Ministry of Cultural and Environmental Heritage (MiBAC) included the Arrone River Valley, the Rio Palidoro and Fosso delle Cadute valleys, and the Furbara Plain in the so-called Identity Agricultural Areas in the Regional Territorial Landscape Plan (PTPR).

The regional document describes the Arrone River Valley and the Fosso di Santa Maria di Galeria as follows: “The area, located between the volcanic complex of the Sabatini Mountains and the Roman Coast Maremma, stretches between Lake Bracciano and the coastal strip near Fiumicino, in the locality of Torre in Pietra. The abundance of water has been one of the great resources of Rome and its territory since its origins. From the Sabatini Mountains to the Boccea plateau, the Arrone River flows, its name derived from the Etruscan root ‘aruns’“. It originates from Lake Bracciano and, after a course of about 37 km, empties into the sea near Maccarese. Based on its geological features, the Arrone basin can be divided into three parts. The upper part, located just south of Lake Bracciano, has a hilly morphology typical of the volcanic reliefs of the region. In the central part, watercourses have carved deep valley incisions and reached the sedimentary layers beneath the volcanic deposits, creating a system of elongated hills. The area includes that part of the valley that represents the transition zone to the coastal plain.

The entire area is a territorial complex of great environmental diversity, where naturalistic river valleys alternate with a vast area of gently rolling hills influenced by the climatic effects of the nearby coastal area. The Arrone Valley, with its resources, has been the site of numerous human settlements tied particularly to rural and agricultural use of the land, evidenced by the Etruscan city known as Galeria, later colonized by the Romans as an agricultural village. By the late 1700s, the village was abandoned, likely due to malaria, and its inhabitants moved approximately 4 km away, founding what is now Santa Maria di Galeria Nuova.

The landscape of the Arrone Valley reflects the Roman countryside of the past century, with pastures, meadows, woods, and hedges alternating with cultivated areas. The landscape, after the hilly area, widens considerably near the confluence of the basin, becoming flat and rich in alluvial deposits. South of the Via Aurelia, the watercourse traverses its final stretch before reaching the sea.

The Arrone Valley has been a focal point for human habitation for thousands of years, as evidenced by prehistoric findings near the emissary’s source and the lower Arrone. A fundamental component of the area is the Castel di Guido complex and its surroundings, a geologically uniform area of significant archaeological, environmental, and scenic interest. Particularly, the current village holds historical and archaeological importance, representing continuous settlement from Roman times to the present day. Another historically and scenically significant area is the Leprignana Estate with its rural centers, a testament to the Roman reclamation of Torre in Pietra (1926–45) led by Senator Albertini.

The land reclamation and the establishment of the rural centers (or Units) of the estate’s productive enterprise shape a unified settlement plan, which varies according to the specialized activities carried out. The agricultural landscape resulting from the reclamation remains relatively intact and stands as a testament to a high-quality territorial agricultural organization designed in its complexity and entirety, including the foundation and decentralization of new housing and rural infrastructure.”

Further north, the Rio Palidoro and Fosso delle Cadute Valleys, the modern boundary between the municipalities of Fiumicino and Cerveteri, extend towards the plain. Although smaller in area, these valleys also impact the municipalities of Bracciano, Anguillara Sabazia, and Rome. The area between the Sabatini Mountains volcanic complex and the Roman Coast Maremma is described as follows:

“The Rio Palidoro Valley resembles the adjacent Arrone Valley in its orthogonal orientation to the coastline and as part of the watercourse network that is a vital resource for Rome and its territory. The Rio Palidoro originates from the Sabatini Mountains and flows into the Tyrrhenian Sea near Passo Oscuro. The ecosystem of the pre-hill areas between Lake Bracciano and the Tyrrhenian Sea constitutes a highly important landscape and natural ensemble. With its orographic sequence from pre-coastal areas to volcanic hills interspersed with wetlands, it is the last preserved example of the typical southern Lazio Maremma landscape. It transitions from reclaimed, orderly agricultural land to ravines and cultivated fields, showcasing a diverse horizon of small uplands that include sites of ancient history, castles, farmhouses, and archaeological remains. The flat areas alternate with the hills, serving as a prelude to the view of the Monti Sabatini in a continuous and fluid manner, connecting the varied and fragmented landscape of the small elevations overlooking Lake Bracciano to the northeast with the vast coastal plain extending toward the Tyrrhenian Sea.”

Rural Environment

In a large area of Fiumicino, the prevailing landscape is rural, characterized by its regular subdivision, the management of water through numerous canals, the hydroelectric plants dating back to the late 19th century, such as the one in Focene, and the typical scattered settlement pattern of farmhouses and/or small rural centers. Here, alongside residential buildings, one can find structures for housing animals, storing tools, and preserving food supplies—distinct features of reclaimed areas.

The large Maccarese-Pagliete plain, covering an area of over 4,500 hectares, was the first to undergo comprehensive reclamation. The Torrimpietra estate to the northeast and, further beyond, the Palidoro estate—both adjacent to the hilly inland areas subject to the Agricultural Reform of the 1950s—share a common history.

Different events that shared a common thread in the wake of the country’s unification: a period of profound and radical changes in the territory. Within a few decades, these transformations deeply altered environments and landscapes, the economy, and the lives of the inhabitants, almost entirely erasing the ancient and long-standing system of large estates. These estates had coexisted with vast wetlands and marshy areas, giving rise to a form of semi-nomadic pastoralism and an agriculture confined to small plots, supporting a sparse, mostly seasonal population that migrated in response to the rhythms of fieldwork and the cycles of malaria.

These more archaic rural landscapes are still visible today in residual areas of the original vast natural lagoon system behind the dune system—now protected as areas of particular value.

The recognizability of the reclaimed landscape, which has remained largely intact, is undoubtedly due to the presence of vegetational elements such as windbreak rows of eucalyptus trees, the regular subdivision of plots, demarcated by drainage and irrigation canals, and the dense network of inter-farm roads. The almost unchanged system of settlement within agricultural centers and farmhouses also contributes to this recognition.

This vast real estate heritage, despite the differences and particularities that distinguish various reclamation projects, has now for nearly a century been an indispensable and strongly identity-defining component of the entire territory. It is perceived as such by the communities living within it, as well as by those who, in different capacities, benefit from its beauty.

Maccarese Reclamation (1925-1938)

Following the first hydraulic reclamation between 1884 and 1889, which involved the hydraulic system’s adjustment and the construction of the water pumps, and later the full reclamation and the creation of the road network, around forty rural centers were designed and constructed, along with farms and facilities for processing and marketing products.

Each center was initially conceived and designed as an autonomous and self-sufficient agricultural unit, featuring residential buildings, stables, silos, warehouses, as well as areas for product processing, an oven, a fountain, and an outdoor space for a garden and vegetable patch, always accompanied by numerous trees.

The architecture of the agricultural centers—whose profile remains the most evident characteristic of the reclamation landscape today—was simple in form and closely aligned with functional needs. The construction techniques and materials used were typical of the landscapes of the Po Valley, from which many of the colonist families initially came.

Torrimpietra Reclamation (1927-1940)

The protagonists of the reclamation were Senator Luigi Albertini, Leonardo Albertini, and Niccolò Carandini, who relied on qualified professionals, specialized workers, and laborers for its realization.

The main innovation was in the organization and planning of the land, viewed in its entirety, with a new approach to housing and rural construction. This shift from temporary to permanent architecture led to the creation of productive units organized in “centers.”

The reclamation and construction of rural centers is the result of a collective effort, which includes, notably in the general architectural design, the work of architect Michele Busiri-Vici, who also restored the Falconieri Castle, which later became the headquarters of the Torrimpietra estate.

The creation of the centers gave form to a unified settlement project, with units differentiating based on the specialized activities they performed. Residential buildings were organized around an open courtyard with a central fountain, and technical buildings were situated in adjacent areas, arranged according to functional and hygienic needs.

To an initial core of centers (Falconieri, Tre Denari, Granaretto, Aurelia, Arenaro, Sant’Angelo), we must add the later settlements of the Tenuta della Leprignana (Breccia, Casetta Cavalle, Quarticciolo Barbabianca, Casal Bruciata). All of these bear witness to a social and economic reality that took architectural form, shaping a phase of territorial transformation in continuity with the past while establishing new rules that today represent one of the key identity markers of the area.

Palidoro Reclamation (1930-1938)

The more than 400 hectares that make up the Palidoro estate, at the time of reclamation, were part of the larger land complex owned by the Pio Istituto S. Spirito.

In terms of timing, the reclamation intervention was the last carried out in the plain stretching from Fiumicino to Ladispoli. The land is crossed by the Via Aurelia, which divides it into a flat part that slopes from the Rome-Civitavecchia railway line to the sea, and a hilly part of great environmental and naturalistic interest.

In this context, the reclamation, which began at the end of the 1920s and ended in 1938, led to the construction of various real estate units, each surrounded by a sufficiently large plot of land to meet the needs of the family unit. Historically, the estates have been allocated to tenants, a practice still in place today.